As I said in the last post, our RV park in Hutchinson, Kansas, Melody Acres, wasn’t much to look at, and I’m not too sure about the wisdom of taking shelter from a tornado in that clapboard office (maybe it’s got a basement?),

but it did have the virtue of being located a mere 2 miles from our first touristy destination of the trip, the Kansas Underground Salt Museum – the salt mines! This is the largest salt mine in the Americas, and lies 650 feet under the surface. It is a remnant of an ancient Permian sea, and part of a vein of salt formed 275 million years ago that runs from Kansas all the way to New Mexico!

During most of the Permian Period, shallow seas covered what is now Kansas. Sea level fluctuated -- sometimes the land was exposed and a terrestrial environment existed; at other times, mudstones (shale) and limestone were deposited in a normal marine setting.

When the Hutchinson Salt Member formed, however, the climate was hot and dry, and the sea was restricted to central Kansas -- probably an isolated arm of the main ocean to the south, or cut off entirely. The rate of evaporation exceeded the inflow of water, and as evaporation continued and the salt content of the water increased, thick layers of salt built up on the sea bottom. It takes about 80 feet of sea water to produce a foot of salt, so it took thousands of years to accumulate the thick salt deposits of central Kansas. Over time, the salt layer was covered by younger rocks.

They started working this mine back in 1923, and today it covers thousands of acres. They take out about 500 tons a day. Roughly 13 trillion tons of salt reserves, about 1,100 cubic miles, underlie Kansas. Underground mines in Kansas range in depth from 600 to 1,000 feet. They use the room-and-pillar method of mining, which begins with a shaft sunk through the overlying rock to the salt deposit. The salt is removed in a checkerboard pattern, in which large square caverns alternate with square pillars of salt that serve as support for the rock above. Approximately 75 percent of the salt is mined, while 25 percent is left for pillars. Blasting breaks the salt into manageable pieces, which are conveyed to crushers and removed to the surface through the shaft with large buckets. Because of the impurities (mostly shale and anhydrite), rock salt is used mostly as road salt for melting ice.

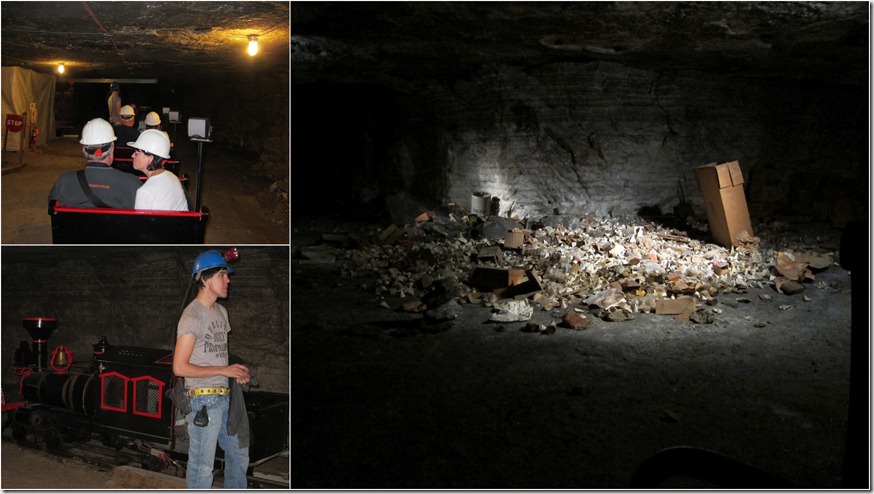

It was our (tongue firmly in cheek) good fortune to hit it on school visit day. We waited while this group of junior highers took off,

then it was our turn to don the hard hats and queue up with the high school bunch to enter the no-frills elevator, which descended the 650 feet in total darkness, much clanking and banging, and a rush of bodies to exit as soon as it hit bottom.

The museum portion of the mines occupies only a small part of the excavations, but even it seems to stretch on and on through long corridors and rooms. The floor here has been paved with a mixture of Portland cement and salt dust.

The excavations are remarkably uniform in height. They accomplished this by following four dark vein lines that extend throughout the salt deposit. Loni is pointing to the lower single line, with the three line group above it. These four were used as horizontal plumb lines to keep the digging even.

The excavating is done by using huge cutting tools and dynamite. To cut into a wall, like the one Loni is standing in front of, they first use a giant chain saw with huge blades that look like a sawtoothed shark. This is used to undercut the wall with a kerf slice (about 8 feet in, and then cut along the wall level with the floor for about 20 feet) in order to provide a small underneath space to permit the stone to drop and, when pulled out, leave a smooth floor. They then drill 26 holes, no more, no less, and fill each one with explosives. All are connected to a single fuse, which has a four minute burn time – enough to allow everyone to get about 300 feet back from the explosion. It all goes kaboom and is scooped up and loaded on big skips to be hauled back to the lifts.

One of the mantras of the mines is that anything that goes down into the mine, stays there. Everything that went down had to be disassembled above and then rebuilt below. They didn’t bother to reverse the process. After all, they have plenty of empty space. The above right is an old car belonging to the mine superintendent. It was used for decades before giving up the ghost and being entombed as an “attraction.”

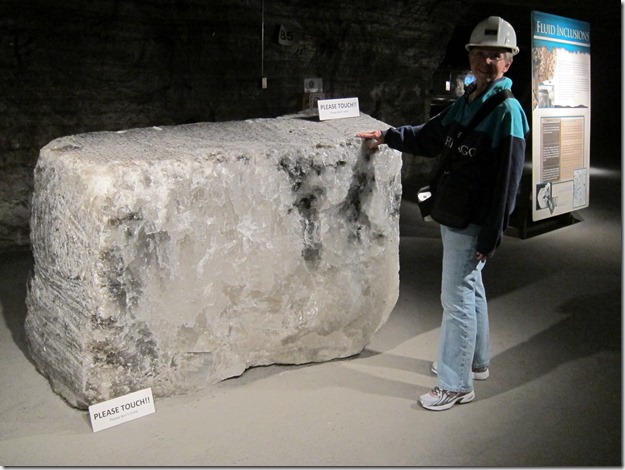

Most of the museum can be done on your own by following the rooms around and viewing/reading the exhibits. Here’s a six-ton pinch of salt.

They also have a couple of optional items: a train ride through a portion of the mine still in its worked state, and a “dark” ride. We figured the dark elevator was sufficient blackness, but opted for the train. It’s a Casey Junior operation, complete with a seemingly Jungle Cruise-type guide (he later dropped the “aw shucks” demeanor and proved to be quite knowledgeable and articulate). The, er, highlight of the ride was this trash pile with items at least as far back as a 1953 calendar. I’ll spare you the low point, which was the impromptu toilet area for those workers who couldn’t wait.

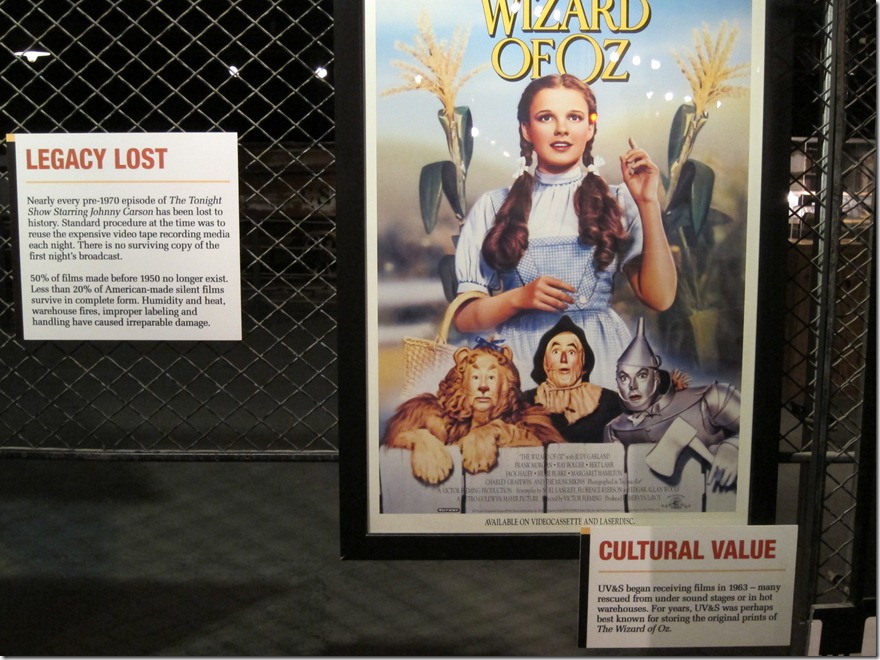

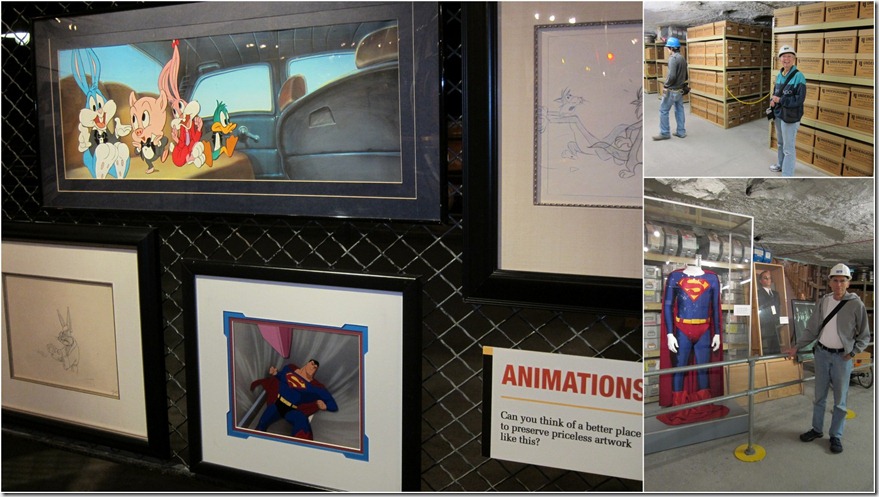

Because of the constant temperature (about 66 degrees) and humidity, and of course its rather impregnable location, a portion of the mines has been long leased ( 50+ years) by a storage company that includes as clients the major movie studios for safekeeping of the original prints of movies and tapes of t.v. shows. The original copy of The Wizard of Oz is down here,

as well as animation cels and costumes from various flics.

Time to quit playing mole people and return to the surface. We had to get on the road and go 90 miles to Abilene (still Kansas), the boyhood home of Dwight Eisenhower and the site of his museum, library, and mausoleum. We have enjoyed extraordinary luck so far on this trip. The usual rule of thumb is that whatever direction we are heading, the wind will be in our face. Headwinds are a disaster for a boxlike RV’s gas mileage. But ever since we set out, we’ve either had calm weather or tailwinds. We even managed 11.1 mpg on one stretch – woohoo! But on the brief run up to Abilene from Hutchinson, we returned to form and started bucking (and rocking, and swaying, and wandering) with the head and cross winds. Mileages since then have gone as low as 8.6. Thank goodness that Kansas has some of the lowest gas prices. We found $3.27 in one spot.

We had to haul butt, as the Eisenhower complex closed at 4:45 and we didn’t get out of Hutchinson until after noon. We did a quick stop at our RV park to check in, then pulled right out and went up the road to the museum. I think Ike is an undervalued president, but he appears to be rising in historians’ opinion as more files and papers are released. Regardless, his was quite a journey from a pacifist religious family with no indoor plumbing until he was 18, to Supreme Allied Commander and President. And not once did he prematurely preen “mission accomplished” on the deck of an aircraft carrier.

The first stop on the grounds was his boyhood home, from about age 1 to 20. This has been preserved on the same site, and contains all original items from his family’s living there, including quilts and throws hand-made by his mother and grandfather. He lived here with four brothers, his parents, and his grandfather (for a while). It may look spacious from the outside, but the rooms are small and cramped.

The piano was his mother’s. In an era when most of them sold for $400 or so, she paid $650 for this one – a fortune! It wasn’t explained how this happened, but the family was not wealthly. I mean, c’mon, they didn’t have indoor plumbing!

The museum was pretty interesting, with a lot of stuff on the war years. One of the nifty items for me was the table on which Operation Overlord – DDay – was planned.

The painting that looks like a medieval religious scene was actually depicting a service that took place several years after the war in which the American military dead were being eulogized by the British, with Ike standing in for them. Curiously, or perhaps not so after all, there was absolutely no mention of Kay Summersbee (sp?), Ike’s alleged paramour during his separation from Mamie during the war.

There is a presidential library housing his papers, etc., and a chapel where Ike, Mamie, and their died-at-age-four first son are buried. Their second son, John, is still alive.

They closed the doors promptly at 4:45, so we split. When we were at the salt mine, one of the docents asked where we were headed next. When he heard “Abilene,” he said we HAD to try a restaurant up there that specialized in fried chicken. We got the name, but not the address. Fortunately, the park map that we picked up from the RV park here had advertisements which included this restaurant. We GPS’d it and took off. It turns out to have been turning out the same menu for 97 years, and they did it well. That’s a whole fried chicken for the two of us!

Needless to say, we took a lot of chicken with us in a baggie.

We were up early the next morning to get in a constitutional before getting on the road. The Covered Wagon RV park was folksy, but clean and handy to town.

Abilene is a small town, but doesn’t have that dying-on-life-support feeling that so many midwestern places have. It’s old --- it seems almost everything was built in 1885 --- but well tended, with few vacant storefronts, and lots of interesting architecture. Ike said once that he was proudest to be able to call Abilene his home.

On our return to the park we came upon this home with the wagon wheel fence.

Adios, Abilene. From here we are just humping it to Indy in a pair of 326 mile days. Oye. Please stop, wind. Please!

Postscript: we made it to Indy in two 326-mile days. Albatross is now ensconced behind Mom’s house and we’re packing for our bus tour of Toronto-Ottawa-Montreal-Quebec City-Niagara Falls. Our birthday present to Mom for her 89th. We leave tomorrow. Posting this from the local library, as Mom has no internet. Allons-y!