Colon (needs an accent over that second “O”) is the sea port on the Caribbean side of Panama near the entrance to the Canal. It was founded in 1855 by Americans as the Atlantic terminus of the Panama Railroad which was being constructed to meet the demand of Gold Rush fortune seekers on their way to California, and was originally called Aspinwall after one of the railroad promoters. It’s not of much interest in itself, other than as a place to dock for shore excursions. In fact, the excursion guide flatly told everyone not to try to walk around as it was just too dangerous. We opted for the Expansion tour so that we could see both the new and the old locks in action. Unlike Cartagena, this tour was the best of the trip.

Our bus was waiting on the dock, and this time we got lucky with our guide, Alexis. He was a younger guy, full of energy and stories, and very knowledgeable about the Canal and the history of his country. He kept up a running commentary throughout the day that was really interesting. Big tip for Alexis! He wisely decided to head first for the new locks in order to beat the crowds that form later in the day. That was a good call, as we had the viewing platform largely to ourselves to establish a good vantage point for observing the ship that was about to make the transit. The viewpoint was at some distance from the actual locks, but did offer a fine overall view. Here’s a panorama shot showing Lake Gatun, where the eastbound ships gather to wait their turn to enter the locks (the beginning of which are at the right).

The ship we’re waiting for is the tanker that lies dead center. To the right of it is a cruise ship that is just making an “in-and-out” transit. It came in from the Caribbean, went through the Gatun locks, will sit here in the lake for the day, then go back east through the locks to the Caribbean. Not all cruises do the full transit to the Pacific like ours did. Here are the new locks, which are 60% larger in both width and length than the old Gatun locks. That’s the Caribbean off to the right. You can see there are three locks in the line, with lake-level water in the near one, somewhat lower in the middle one, and down at sea level in the far one. The square basins to the left are for recycling a large portion of the lake water used to fill the locks so that it doesn’t all run into the sea. This helps keep the lake at a level sufficient to maintain operations.

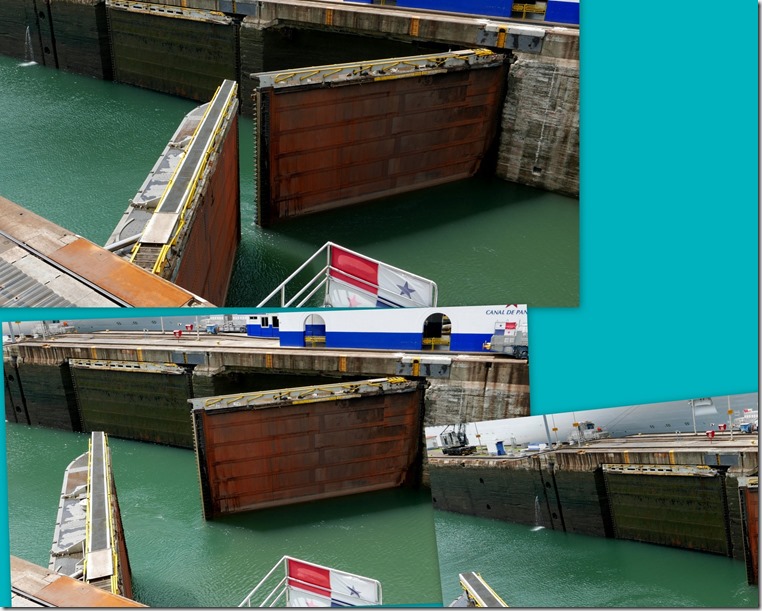

Unlike the old locks, which use clamshell doors to close off the lock basin, the new locks use sliding “walls” that fit into a recessed pocket when open, and slide across the canal channel when closed. When closed, the top of the wall becomes a roadway for crossing the Canal, as there are no bridges. These locks use double doors (see the one on the right in this pair, which is fully retracted) to seal in the ships. This provides a safety backup in case of a failure. These doors open or close in about 5 minutes, are 57 meters long and 10-12 wide.

The new locks opened for business on June 26, 2016. They don’t replace the old locks, which are still in use for the smaller vessels, but rather supplement them with room for larger capacity ships. The waterway for the old locks runs parallel to this one, and can be seen by the cruise ship using the old locks about a half mile away in the background.

Ships that fit the old locks are called Panamax ships, and those that travel the new are Neopanamax’s. Typically, the former can hold up to 13 cargo containers across the width of the ship, and the latter can sport up to 18. The ship we watched go through wasn’t a container ship, but a liquified gas tanker. By the time it made its way into the locks, our empty viewing area got quite crowded with newcomers, all trying to wedge their way up to the barrier to get a clear shot. I held my ground. See the ship in the right background using the old locks.

The tugboats don’t actually tow or retard the ship; it’s under its own power. The tugs’ function is to keep the ship centered in the locks.

The lowering of the first lock. This ship wasn’t particularly big, so they had plenty of room on both sides, unlike the tight squeezes common to the old locks, where barely two feet of room exists on each side.

Both of us thought the old locks were by far the most interesting. For one thing, you could get virtually right on top of them, although we were told that the viewing here will be ended next year and you’ll only be able to go to the new locks. That’s a major bummer. These locks have the atmosphere and the history that are what tourists want to see. The new locks, while impressive, are like watching a movie on a big screen: sterile and remote. The gates at the old locks are clamshells, and the doors that form them are the original steel gates built in Pittsburg a century ago, and still in good shape!

You can see the tight fit on this cruise ship in the left channel; also see the tanker down at sea level waiting to come into the right channel. It takes about 45 minutes for a ship to transit through one lock. Since there are three in a row here, about 2 hours and a quarter to get from the Caribbean to Lake Gatun.

Along both sides of each canal basin there are railroad tracks. Small donkey engines run along these tracks and perform the same function as the tugboats on the new locks. They keep the ships centered in the locks, but don’t provide propulsion power. The new ones of these cost $2 million each. You can see the lines attached to the forward engine; number 172 in the foreground has shorter ones attached to the side. From the scrapings on the sides of the ship and the lock walls, the engines do a good job but not a perfect one.

The tracks on which the trains (two of them in this shot) run (including hills to go “up” the locks); note the tight fit of this cargo ship in the lock.

The cargo ship (note 13 containers wide) is headed West, the cruise ship to the East.

The closed clamshell gate and the empty basin on other side.

I sure hope that Panama reconsiders the closing down of this viewing facility for the old locks. The up-close-and-personal nature is a far better experience than at the new locks. Tourism accounts for a larger percentage of income for Panama than even the Canal. That’s surprising, given the cost for a transit. Our ship will pay nearly $400,000 for our transit! The bigger cargo/tanker ships pay nearly $500,000. Wow. Even at those prices, it’s cheaper than going around the Horn. Pretty good deal for the Panamanians, who were handed the Canal, lock, stock and barrel by Jimmy Carter, free of charge. To their credit, they’ve done a good job maintaining the old canal, dredging the lake, repairing the locks, and, of course, building the new locks at tremendous expense. Two dangers lurk for the future of the Canal as a moneymaker: the proposed Chinese canal across Nicaragua, and the possible opening of a global-warming sea route across the top of Canada. The Chinese proposal was just put on hold after the estimated costs went up by 50%, and is probably dead. The sea route? Keep tuned. With Trump cozied up to the oil industry, it may come sooner than we think. Note in this shot of the visitor facilities the old original donkey engine to the right of the building.

As we got on the bus, we spotted a tail-high critter to the side. Alexis told us it was a coatimundi, and he got off to throw bits of our snack muffins to it. We promptly were deluged by a family of coatimundis who have probably been habituated to this meal op. For us, it’s off to the ship for our transit tomorrow!

No comments:

Post a Comment