Taking advantage of the weather, we offloaded the scoot and took off for Astoria, which is home to two things we wanted to see. The trip down, although only 20 miles or so, proved to be perhaps our scariest scoot ride to date. Although there was no rain, the wind picked up considerably as we neared the mouth of the Columbia, and was really blowing in gusts as we prepared to cross the 4.5 mile bridge that spans the “bar",” which is where the ocean and the river meet. This is the start on the Washington side. Smaller craft can pass under these arches, then the bridge drops down to water level for a couple of miles, before soaring to the span where the big ocean freighters pass under. See the rise at the end? That’s not going up a hill on land.;

that’s the upgrade to the r-e-a-l-l-y high part.

Anyway, we were being blasted by the wind gusts, on a wet roadway, with trucks barreling by from the other direction. I kept it down to 45 (limit was 50) and some (unmentionable) Washington driver behind me floored his pickup, roared past, spraying water, and cut right in front. All that to catch up to the cars that were about 200 feet ahead. We leaned, bobbed, and danced our way across and were very happy to be off that thing. Fortunately, on the way home, the wind disappeared and it was a piece of cake.

Can’t say as the terror was worth it for our first stop, the Lewis & Clark encampment reproduction. The visitor center was ok, but we both have read “Undaunted Courage” and were pretty familiar with the story. They truly were iron men in wooden, well, canoes. We didn’t learn much new from the exhibits, save for the fact they carried a huge Newfoundland dog with them. Neither of us remembers that from the book. The reproduction of their fort was again, ok, but not much to make a special trip for.

We went back to Astoria, cruised the main drag and decided to stop for lunch. Good call. We found a great little cafe that made interesting quesadillas, what appeared to be excellent sandwiches, and homemade desserts! We split a smoked chicken/apple/walnut quesadilla, two bowls of clam chowder (alas, the thick kind, which I don’t favor, but still good), and a piece of lemon pie, made with the whole lemon innards, not just the juices. Delicious!

Fortified (actually, stuffed is more like it), we moved on to the Columbia River Maritime Museum.

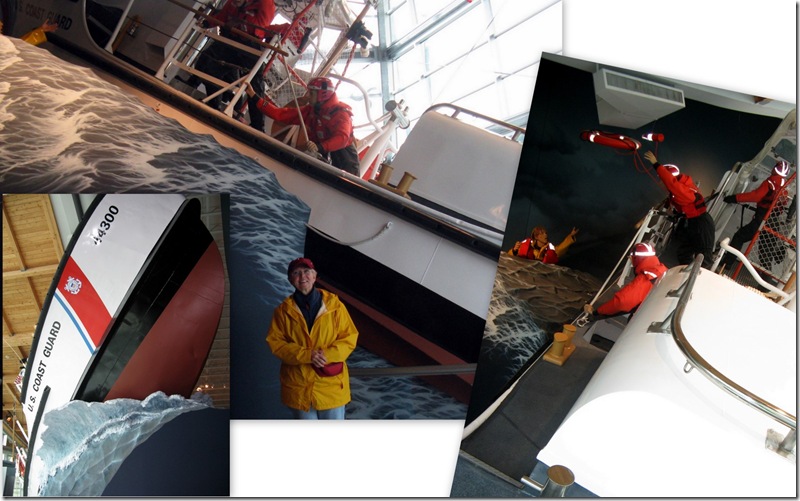

The mouth of the Columbia River is regarded as the most hazardous waters in the U.S. It is called the “Graveyard of the Pacific.” Hundreds and hundreds of ships and boats have foundered here because of the violent conditions. The mighty Columbia here tries to exit into the ocean, in a fairly narrow space. The ocean tides and winds, however, try to force the river back, resulting in ferocious waves at the juncture, called the “bar.” The waters are so treacherous, with constantly shifting channels and sandbars, that all major ships have to be guided in by a professional “bar pilot,” who is ferried out on a powerful small craft that races alongside the ship, where a dangling rope ladder awaits the pilot, who has to grab and jump onto it. The waters here are also recognized by the Coast Guard as the worst in the U.S., so all of their training of their rescue craft sailors is done here. If they can hack this, they can work anywhere. They have a rather dramatic display of a rescue, using an actual boat that served for 29 years, and showing the incredible wave-mountains that these boats have to deal with.

The museum had lots of displays of navigation lights,

models of ships that went down here, artifacts from wrecks,

films of the boats in rough seas,

real boats that worked these waters,

and nautical lore. At last, I finally know how to tie a bowline!

Docked next to the museum was the lightship Columbia, that spent three decades bobbing and tossing at anchor just outside the entrance to the river, warning boats of the dangerous waters. In olden days, the same job was done by iron men in wooden sailing ships, with no motor power, just anchors to keep them in place, until they ripped loose. Regardless of Columbia being made of metal, it’s sailors were made of the same iron.

In the late 70’s, these ships were replaced by floating beacons like you can see at the left of the pic above. The crew spent two weeks onboard, then had one off, before starting over. The pitching and rolling were so bad that even the most experienced sailors got sick. I can’t imagine doing that job for long, even with luxurious quarters like these.

Again, this is another of those unusual museums unique to the Northwest. We thoroughly enjoyed it and do recommend making a detour to see it. After we finished on the lightship, we looked over towards our own small craft, and got underway.

No comments:

Post a Comment