Gatun Lake is situated in the valley of the Chagres River. It was formed by the construction of the Gatun Dam in 1907–1913. The damming of the river flooded the originally wooded valley; almost a century later, the stumps of old mahogany trees can still be seen rising from the water, and submerged snags form a hazard for any small vessels that wander off the marked channels. The lake has an area of 164 sq mi at its normal level of 85 ft above sea level; it stores 183 billion cubic feet of water, which is about as much as the Chagres River brings down in an average year. Here’s another view of the dam, with the river running off behind:

Ships waiting for their turn to enter the Gatun locks; the middle one is really riding low.

There’s not a whole lot to see while crossing the lake to get to the Cut. Mostly it’s meandering shoreline with estuaries branching way off to the sides. Too bad it was such a hazy day, not great for photography.

The Canal has an elegantly simple means of navigation across the twisting path the ships must follow in order to stay in the dredged channel. On the islands or the main shore are a series of verticle markers, visible from a great distance. Once a set of markers is lined up so that it looks like a solid stripe, the ship knows it is on the proper course in the lake. It follows those markers until the next set appears, then it alters course to make those line up. See the offset markers in the top half below, meaning the ship is not precisely on course and needs to come starboard a bit. In the bottom half, the markers are (almost) lined up and appear as an unbroken vertical stripe. Actually, we need to come port a bit. The approaching ship is keying on a set of markers behind us.

The Gaillard Cut, also called Culebra Cut, is an excavated gorge 8 miles long across the Continental Divide. It’s named for David du Bose Gaillard, the American engineer who supervised much of its construction. The unstable nature of the soil and rock in the area of Gaillard Cut made it the most difficult and challenging section of the entire canal project. Workers who labored in temperatures of 100 or more degrees used rock drills, dynamite, and steam shovels to remove 96 million cubic yards of earth and rock as they lowered the floor of the excavation to within 40 feet of sea-level. Hillsides were subject to unpredictable earth and mud slides and at times the floor of the excavation was known to rise precipitously simply due to the weight of the hillsides. The well-known Cucaracha slide continued for years and poured millions of cubic yards into the canal excavation. Although the hillsides have been cut back and their angles decreased over the years to lessen the threat of serious slides, dredging remains a necessary part of canal maintenance in order to insure an open channel. This shot shows some of the cut-backs, unfortunately taken through the blue-tinted windows of the lounge.

Work continues on cutting back the banks to reduce slides and erosion.

Approaching the end of the cut, the difficult nature of the dig is displayed by these huge hillsides. In the background appears the Centennial Bridge, opened in 2004 to supplement the only other crossing, the Bridge of the Americas (the small service bridges built in the lock structures at Miraflores and Gatún Locks are only usable when the lock gates are closed and have limited capacity).

For perspective, there’s a bus or truck crossing right in the center of the bridge.

After passing under the bridge, we entered the Pedro Miguel locks, the middle set of the three locks series. We again are using the narrower old locks, on the left. To the right of the picture you can see the much broader new channel for the new super lock in this set. The PM lock is a single one. There is an oncoming ship in the left lock, but you can only see its superstructure as it is at the lower level.

The procedures and equipment at the PM locks are much the same as at the Gatun ones, so I won’t lard up the blog with similar photos.

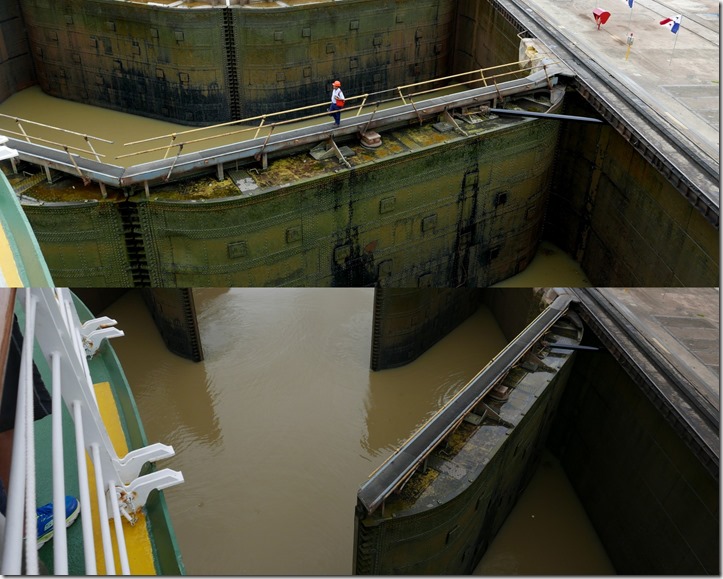

I did want to include, however, the famed “rubber bend” in the lock.

Below is the view straight down the side of the ship. One foot of clearance! I gripped the camera fairly tightly. That’s the top of one of the little donkey engines down below.

Looking back while in the PM locks, towards the Centennial Bridge, with the new lock channel on the left.

Turning back the other way, we are immediately approaching the Mira Flores locks, the last of the series. In the right background is the Bridge of the Americas, the first one to cross the canal. The channel for the new locks is out of the picture way off to the right.

Peeping over the hills is the only view we had of the skyscrapers of Panama City, which lies on the Pacific. From what we heard from other travelers, we aren’t missing anything.

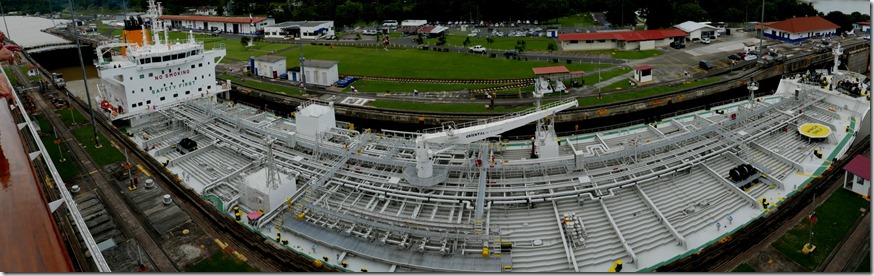

Entering the Mira Flores locks.

The water goes down, the workers go home to dinner, and the final gate opens to let us out.

Exiting the lock, into the bay just before the Pacific Ocean. The roiling water is from the discharge of the lock water back into the sea as our lock emptied.

We’re through! Under the Bridge of the Americas and we’ll be in the Pacific. Farewell Panama Canal, you were a very neat ride!

Happy Cruisers.

2 comments:

Love the picture of the two of you, and the one of Jon! Looks like you had an amazing trip!

Love the picture of the two of you, and that one of Jon with his food! Those eyes! ha ha Thanks for this amazing journey! I felt like I was there!

Post a Comment